Kenya’s economy is entering a phase where adaptation is no longer optional, but structural. Intelligent technology is no longer arriving at the edges of economic life; it is settling at the center. Algorithms now influence lending decisions, automation reshapes production, and data-driven systems quietly determine efficiency, pricing, and access. The question before us is not whether technology will advance, but whether the economy it is transforming is built to absorb the change without tearing at its seams.

Economic readiness is often misunderstood as technological adoption. When new systems appear, success is measured by how quickly they are deployed or how much productivity they generate. But technology does not operate in a vacuum. It interacts with labor markets, education systems, informal enterprises, and regulatory frameworks. An economy that adopts intelligent systems without aligning these foundations risks accelerating growth in some areas while destabilizing others.

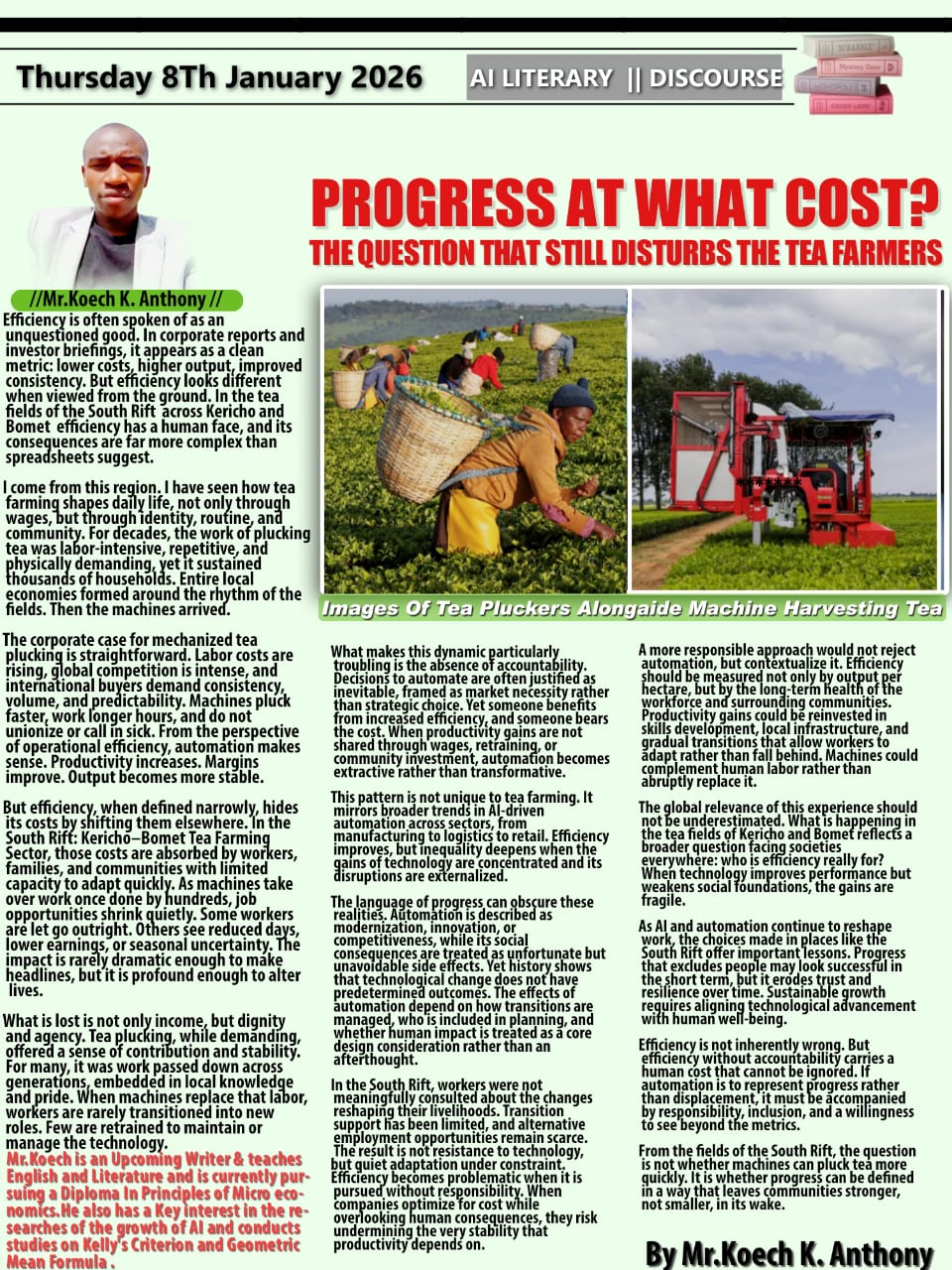

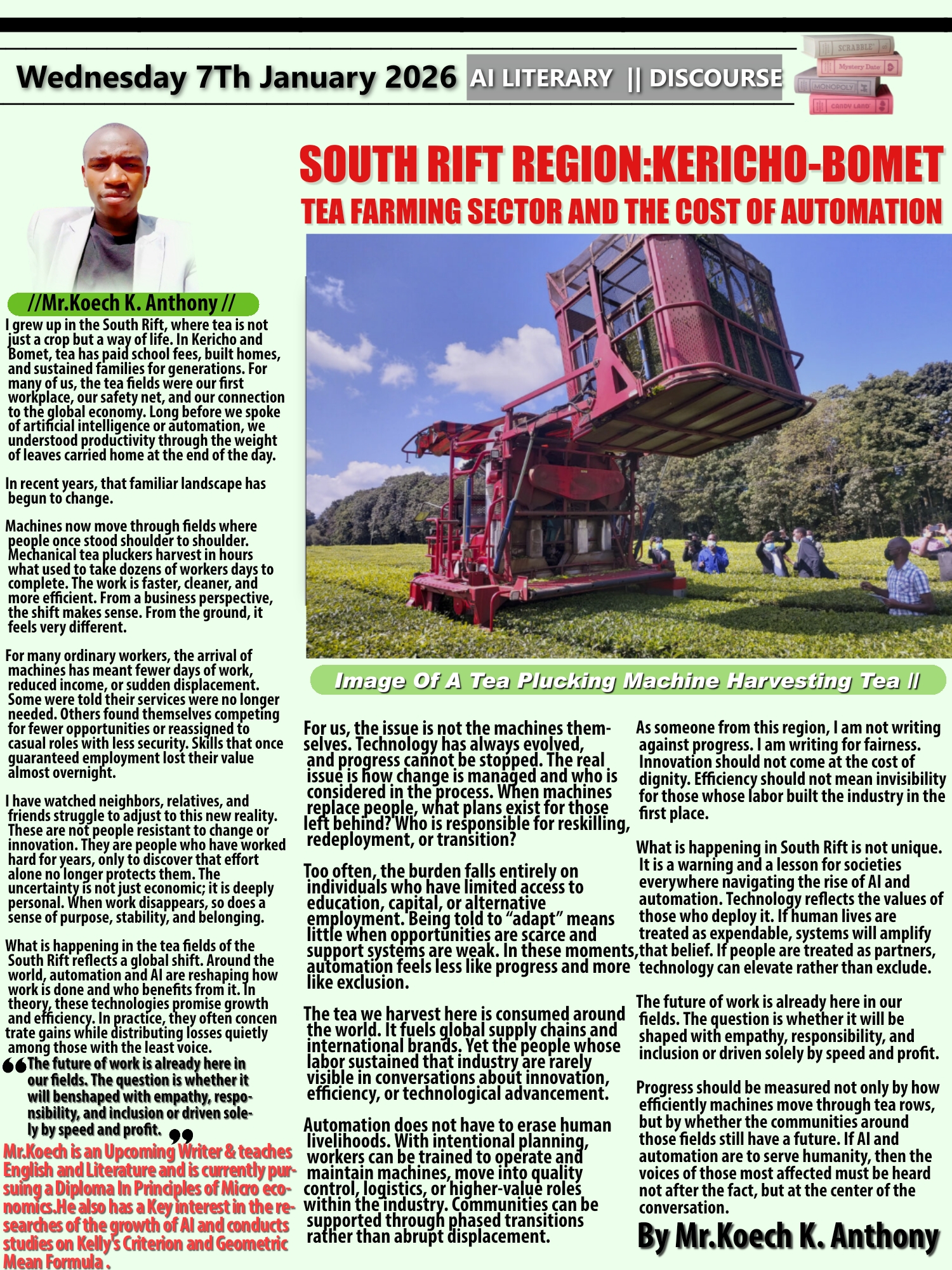

Kenya’s economic structure makes this tension particularly visible. The economy remains deeply labor-driven, with agriculture and informal trade employing millions. Intelligent technology introduces a different logic one that rewards scale, data, and precision over volume of labor. This shift can improve efficiency, but it also exposes a mismatch between how value is increasingly created and how livelihoods are currently sustained. When productivity rises without a corresponding pathway for workers to transition, efficiency becomes exclusionary.

What makes this moment different from previous technological waves is speed. AI-driven systems evolve faster than institutions adapt. Skills become outdated quickly. Entire job categories can shift within years rather than decades. Yet economic planning often assumes gradual change. The result is a growing gap between policy timelines and technological reality, leaving individuals to navigate disruption with limited support.

The informal economy, frequently celebrated for its resilience, sits at the center of this challenge. Digital platforms, mobile payments, and algorithmic coordination are already reshaping informal work. While some benefit from expanded reach and efficiency, others face intensified competition and reduced bargaining power. Without intentional inclusion, intelligent technology risks formalizing inequality rather than opportunity.

Readiness therefore requires more than infrastructure and innovation hubs. It demands investment in adaptability as an economic asset. Skills development must be continuous, practical, and connected to real demand. Education systems must prioritize learning how to learn, not merely mastering static content. Economic policy must recognize reskilling and transition support as growth strategies, not social add-ons.

Equally important is how productivity gains are distributed. Intelligent technology increases output, but it does not automatically improve livelihoods. When efficiency gains are captured narrowly, they weaken social trust and reduce economic resilience. An economy is strong not when it grows quickly, but when it can absorb shocks, redeploy talent, and maintain stability through change.

Kenya has demonstrated before that technology can be a democratizing force. The success of mobile money was not simply technical; it worked because it expanded access and aligned with everyday economic behavior. Intelligent technology presents a similar opportunity, but on a broader and more complex scale. The difference will lie in whether policy, education, and enterprise move in coordination or in isolation.

There is also a governance dimension to readiness. As algorithms influence credit, employment, and resource allocation, questions of transparency and accountability become economic concerns. Trust is an economic input. Without it, adoption slows, resistance grows, and innovation becomes fragile. An economy shaped by intelligent systems must ensure that decision-making remains explainable and contestable.

Ultimately, readiness is not about predicting every technological outcome. It is about building systems that can adjust as conditions change. Economies that succeed in the age of intelligent technology will be those that treat people as assets to be developed, not costs to be optimized away. Growth that overlooks human adaptability is not sustainable; it is temporary.

Kenya stands at a point where choices matter. Intelligent technology can deepen productivity while widening inequality, or it can support inclusive growth by design. The difference will be determined not by the sophistication of the machines, but by the foresight of the institutions guiding their use.

The age of intelligent technology does not ask whether economies can grow faster. It asks whether they can grow wiser.

Economic readiness is often misunderstood as technological adoption. When new systems appear, success is measured by how quickly they are deployed or how much productivity they generate. But technology does not operate in a vacuum. It interacts with labor markets, education systems, informal enterprises, and regulatory frameworks. An economy that adopts intelligent systems without aligning these foundations risks accelerating growth in some areas while destabilizing others.

Kenya’s economic structure makes this tension particularly visible. The economy remains deeply labor-driven, with agriculture and informal trade employing millions. Intelligent technology introduces a different logic one that rewards scale, data, and precision over volume of labor. This shift can improve efficiency, but it also exposes a mismatch between how value is increasingly created and how livelihoods are currently sustained. When productivity rises without a corresponding pathway for workers to transition, efficiency becomes exclusionary.

What makes this moment different from previous technological waves is speed. AI-driven systems evolve faster than institutions adapt. Skills become outdated quickly. Entire job categories can shift within years rather than decades. Yet economic planning often assumes gradual change. The result is a growing gap between policy timelines and technological reality, leaving individuals to navigate disruption with limited support.

The informal economy, frequently celebrated for its resilience, sits at the center of this challenge. Digital platforms, mobile payments, and algorithmic coordination are already reshaping informal work. While some benefit from expanded reach and efficiency, others face intensified competition and reduced bargaining power. Without intentional inclusion, intelligent technology risks formalizing inequality rather than opportunity.

Readiness therefore requires more than infrastructure and innovation hubs. It demands investment in adaptability as an economic asset. Skills development must be continuous, practical, and connected to real demand. Education systems must prioritize learning how to learn, not merely mastering static content. Economic policy must recognize reskilling and transition support as growth strategies, not social add-ons.

Equally important is how productivity gains are distributed. Intelligent technology increases output, but it does not automatically improve livelihoods. When efficiency gains are captured narrowly, they weaken social trust and reduce economic resilience. An economy is strong not when it grows quickly, but when it can absorb shocks, redeploy talent, and maintain stability through change.

Kenya has demonstrated before that technology can be a democratizing force. The success of mobile money was not simply technical; it worked because it expanded access and aligned with everyday economic behavior. Intelligent technology presents a similar opportunity, but on a broader and more complex scale. The difference will lie in whether policy, education, and enterprise move in coordination or in isolation.

There is also a governance dimension to readiness. As algorithms influence credit, employment, and resource allocation, questions of transparency and accountability become economic concerns. Trust is an economic input. Without it, adoption slows, resistance grows, and innovation becomes fragile. An economy shaped by intelligent systems must ensure that decision-making remains explainable and contestable.

Ultimately, readiness is not about predicting every technological outcome. It is about building systems that can adjust as conditions change. Economies that succeed in the age of intelligent technology will be those that treat people as assets to be developed, not costs to be optimized away. Growth that overlooks human adaptability is not sustainable; it is temporary.

Kenya stands at a point where choices matter. Intelligent technology can deepen productivity while widening inequality, or it can support inclusive growth by design. The difference will be determined not by the sophistication of the machines, but by the foresight of the institutions guiding their use.

The age of intelligent technology does not ask whether economies can grow faster. It asks whether they can grow wiser.